|

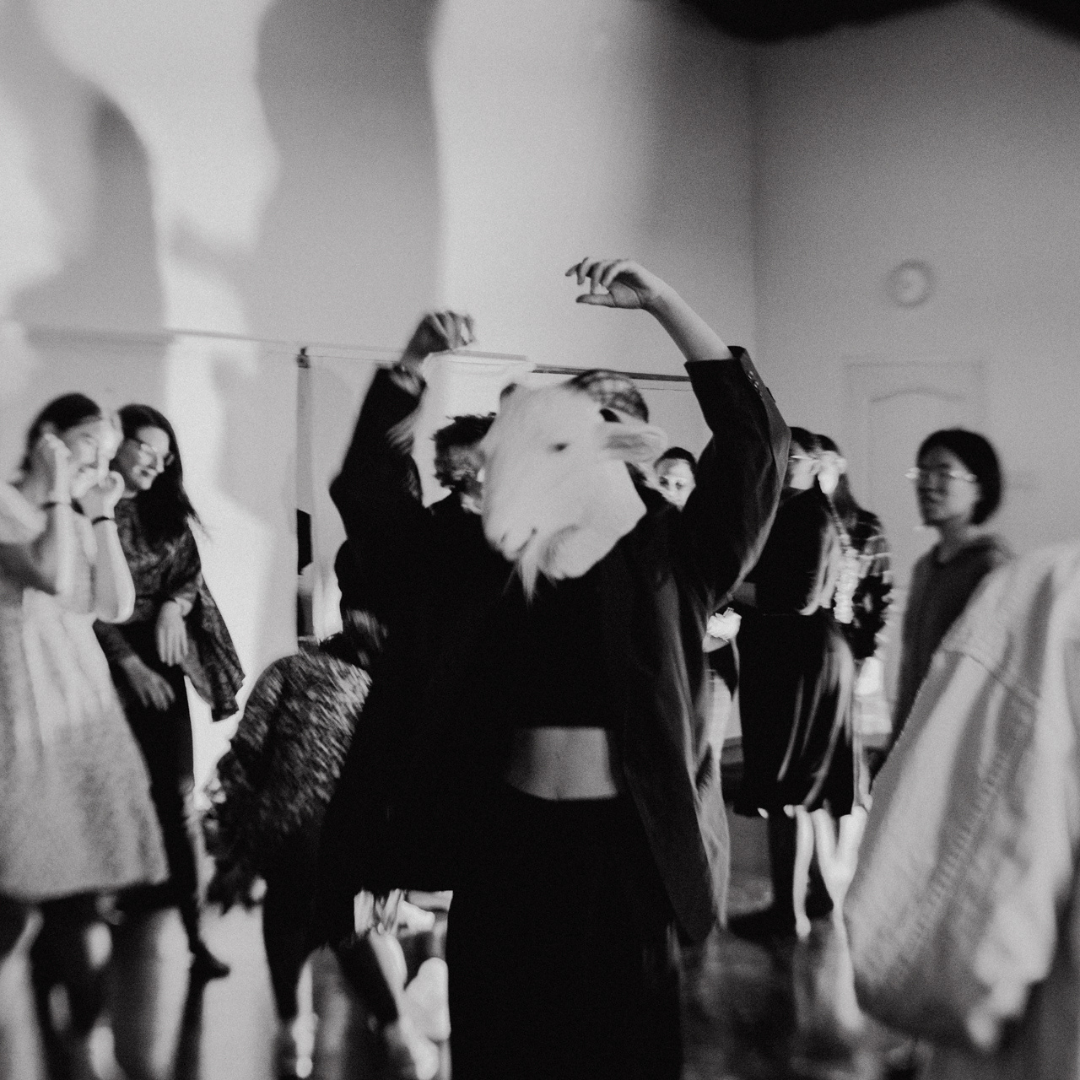

My Fight Clubs serve as arenas for reappropriation. Here, through practices like self-defense, wrestling, and play fighting, we not only reclaim but also assert our ownership of voices, bodies, emotions, and spaces that rightfully belong to us but have been unjustly taken away.

My Fight Clubs are also brave spaces where we dare to challenge societal norms and personal limitations. In this nurturing and secure environment, participants are encouraged to explore their physical and emotional boundaries without fear of judgment, allowing for deep personal growth and empowerment. My Fight Clubs are political soft spaces for tactical and strategic thinking, where we learn how to navigate power dynamics, resist domination, and stand up for ourselves. Here, I empower individuals to become agents of transformation, starting with their own personal development. My Fight Clubs are spaces of leadership outside of the capitalist framework. Here, we explore our unique leadership styles and reclaim agency, fostering confidence, and developing the skills necessary to occupy space and effect change.

0 Comments

A successful workshop is not necessarily one where we laughed a lot, where the atmosphere was pleasant, where human relations were easy, and where we had a good time. For me, a successful workshop is a useful workshop—a space where we learned, unlearned, and relearned things, regardless of the circumstances.

There is no hierarchy between theoretical, practical, technical, or methodological workshops, just as there is no hierarchy between lexical knowledge and personal experience. They are simply different entry points, each valuable in its own way. The question is not what you learn in a workshop, but how you learn it. The role of a teacher (Unlearning Facilitator) is not only to transmit knowledge, tools, experiences, but also to invent a framework, to choreograph a context that encourages individual initiative, responsibility, and independence. A useful workshop is one where we make progress compared to ourselves, not others. It’s a place where we are encouraged and respected, where we can move forward and grow at our own pace. It’s important to remain open to the idea that sometimes the learning and unlearning will come from unexpected sources, and the lesson may not be where you anticipate it to be. Egy valódi experimentális munkafolyamat az olyan, hogy elkezdesz valamit, de fogalmad sincs mi lesz belőle. Olyan eszközökhöz is nyúlsz, amikhez amúgy nem szoktál. Kipróbálsz dolgokat, amiket egyáltalán nem tudsz kontrollálni, mert vagy nincs rutinod a médiumban, vagy nem tudod hogy a dolog hogy fog elsülni, miből mi lesz. Az experimentális munkafolyamat bevállalós, nem azt keresed, hogy mi néz ki jól, mi a szép, hogy mi a hatékony, nem reprodukálod azt, amit tudsz, ami bejáratott, hanem ismeretlen vizekre evezel. Rizikó, elveszettség érzése, rengeteg kudarc, de csodálkozás, ráébredés, adrenalin, meglepetések sora, ez az experimentális munkafolyamat!

|

Author"Born in Budapest (Hungary) in 1983, I graduated from the ENSAPC Art School (France) in 2016. As an artist, researcher, and community activist, I harness the power of art for connection, education, and activism. My practice spans various mediums, including image, object, and performance. I create full-length visual and dance performances, short-format pieces, and immersive experiences, while also creating spaces for non-formal education outside of traditional academic heritage. Over the past two decades, I've founded the School of Disobedience, established my own performance art company (Gray Box), and launched the annual Wildflowers Festival. I embrace everything unusual, unexpected, and nonconformist. I am not kind with assholes and have learned to forge my own path. I am here to guide you in thinking outside the box and achieving independence. To me, the real party is outside the confines of the established canon." Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed